Oxford’s admissions reforms won’t solve the problem but grammar schools would

If we want to increase the number of poor students attending Oxford, we must bring back grammar schools.

A worryingly low number of students from poor backgrounds are able to access the best universities in this country, such as Oxford. Confidence may play a part in this though it is unlikely to be a predominant factor, despite recent claims to the contrary. The main reason is that, unlike the rich, who can afford private education or high house costs in catchment areas of good comprehensives, the poor are (mostly) subjected to low standards of education; too low to enable clever poor students to reach their potential.

As I discussed in my article for our second print issue:

The best schooling [today] is reserved for the richest in society. A shocking report by the Sutton Trust (2017) found that ‘the catchment area of a top 500 [comprehensive] school [attracts] a premium of around 20% compared to house prices elsewhere in the same local authority.’ In other words, to get your child into one of these higher-quality, non-fee paying, non-selective schools, you must be able to afford to live in a house £46,000 more expensive on average than others in the surrounding area. Unsurprisingly, though regrettably, this means that ‘43% of pupils at England’s outstanding secondaries are from the wealthiest 20% of families’ (Teach First, 2017).

Likewise, in the home, some from poor backgrounds may be pushed to read, perhaps even to play a musical instrument, but this is increasingly rare. More and more families do not even sit around a table and talk whilst eating dinner, preferring instead to gawp at a TV.

The result of this (with regards to university admittance) is as follows (again, from my March article):

A recent report found that only 4 in 10 attending the top universities went to academies or comprehensives, which in any case will likely have been located in the wealthy areas described above, inaccessible to the clever poor. The other 6 in 10 were lucky enough to have parents who could afford to pay directly for a better education through private fees, thus making them more appealing for outstanding universities which, understandably, wish to maintain their high academic standards.

Likewise, a study concluded last December that Oxbridge recruit more students from eight top schools than they do from 3,000 other schools put together (Sutton Trust).

In an attempt to reverse this trend, the University of Oxford is introducing a new scheme, under which a quarter of its students must, by 2025, have come from poor backgrounds. I discuss in full the effects this patronising scheme will have on the university in our fourth print issue (out now). In sum, the university’s standards are bound to decline; the most talented tutors – not wanting to teach reductionist foundation courses – will look to teach elsewhere and attainment levels will fall. Not suddenly, of course. The full effects will only be calculable when it is too late.

Interestingly, many commentators who have defended this scheme highlight the confidence held by rich private (or, indeed, good comprehensive) school students regarding their chances of getting into Oxford. This was not always the case. I copy here an interesting segment of journalist Anthony Sampson’s great work the Anatomy of Britain (1962):

Ten years ago half the boys at Eton went to Oxford and Cambridge: now it’s only a third. ‘They [emphasis added] are giving us a terrific run for our money,’ one public school headmaster told me: ‘I’ve been trying to get my head boy a place at Oxford for the last few months.’ The public schools, even Eton, have been forced to stiffen their entrance requirements, and they now throw out stupid boys quite ruthlessly.

(p. 209).

Who, then, is this they? Grammar schools.

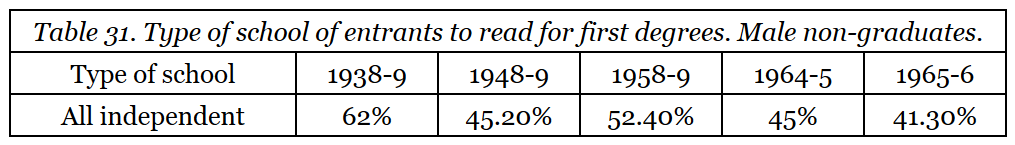

Again, I won’t spoil too much of the fourth issue, but will reproduce this table, from the Franks Report (1966):

Franks Report (1966), volume two, statistical appendix, page 47, table 31, showing the number of Oxford entrants from private schools DECREASING as more were accepted from grammar schools.

Grammar schools were made available to all by the Education Act, 1944. After this, the number of private school students who got into Oxford fell in 20 years by over 20 percent. Grammar school students were taking their places.

It is worth noting also that, despite what many now believe to have been the case, grammar schools were not dominated by the middle classes when they were in their prime (that is, before being cynically gutted out of poor areas by politicians whose own children’s educations were well looked after). Instead, half of their places were taken by clever poor children (Gurney-Dixon Report, 1954). These were given the tools they needed to reach their educational potentials, as the above shows.

If we want to increase the number of poor students attending Oxford (as we certainly should), this is the road we should go down. Instead, our educational leaders choose silly, patronising quotas which will, in the end, lead to the demise of such great institutions.